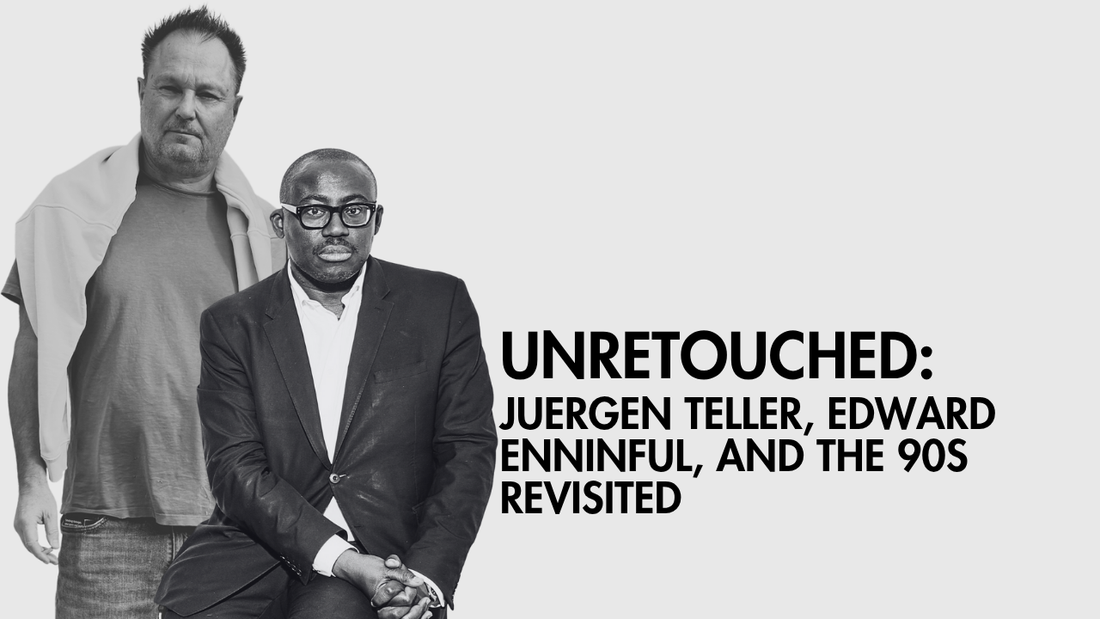

Unretouched: Juergen Teller, Edward Enninful, and The 90s Revisited

Share

Written by Massimo Casagrande

“England really welcomed me, in Germany you had to climb up the ladder, have

certificates, be an assistant. In England it didn’t matter. You showed your work and

they gave you a chance.”

The 90s were messy, honest, and gloriously unfiltered. A decade where we learned

who we were through magazines, the music scene, grainy photos, and the chaos of

culture itself. So when Juergen Teller and Edward Enninful took the stage at Petit

Palais during Art Basel Paris to revisit that era, it didn’t feel nostalgic; it felt like a

reminder of when things were raw, imperfect, and alive.

Teller began the conversation by recalling his arrival in London from a small German

village, barely speaking English, and how his story started out not with fashion, but

record sleeves.

Sinéad O’Connor’s Nothing Compares 2 U became his entry point, and he had been

welcomed by the London creative circle that defined the decade: Judy Blame, Zoe

Bedeaux, and Ray Petri. They were the creative energy that moved between

photography, styling, and sound. “They let me be part of it,” he said. “That warmth

meant something,” remembering the openness of that scene.

Teller says he wasn’t grunge. He was an observer, part of the scene yet always

outside of it, photographing it as it lived. As he spoke, images of the 90s flashed on

the screen: a young Chloë Sevigny, Harmony Korine, a pink Kate Moss, Kurt Cobain

and Courtney Love, and an iconic Kristen McMenamy naked for Versace. A

contradiction to his words. They were a reminder that his refusal to belong helped

define the look of that decade.

Enninful smiled, reminding him, “You said you were an outsider, and I said you were

an outsider but also the ultimate insider, because everybody wanted to work with

you.”

“Yeah, I guess. I mostly said no,” Teller replied, “Because, you know how it was, you

had to think, what do you want to do? And when you're young, it takes a long time to

think about what you want to do. I didn't want to churn out the work.”

It was a time of experimentation before everything became categorised or turned into

a commodity. “You went to record stores and studied sleeves; magazines were few,

so you had to really look,” he recalled. “Things were slower, and they could develop

in time. You had to survive doing what you believed in.”

Teller’s reflections carried a quiet pride in process, in the craftsmanship of

photography itself. He described learning light, film, and printing as a kind of

apprenticeship in patience. What struck me most was his insistence on time, and

how creativity once relied on slowness, and how that rhythm has disappeared. “You

need time to play,” he said. “You need time to fail and learn from your mistakes. It’s

good to go to a bad movie, because you learn how bad it is.” That idea of learning

through failure hung in the air like a quiet protest against today’s culture of

optimisation, a reminder that everything was already there, if only we could see it.

That sense of restraint, and of knowing when not to belong, defined much of his

journey. When American Vogue flew him over on Concorde, he quickly realised how

narrow the system could be. “You’re suddenly in New York and you do not

photograph black and white, it has to be colour,” he said. “I got bored by it. So

instead of me flying over the ocean, I thought, why don’t I be in the studio and turn

those things upside down and let them come to me.”

What followed was Go-Sees, his year-long conceptual project that blurred

documentary, portraiture, and fashion. “I was sure it was good,” he said.

“Conceptually interesting, even politically. The same power it had when I started

working with Helmut Lang.”

That partnership, built in 1993, with Helmut Lang redefined visual language: raw,

minimal, intimate. He shot what was already there: models arriving, waiting, leaving.

No fantasy, just reality reframed. Helmut was part of his “German connection”, a

small, tight-knit circle that included Ellen von Unwerth, Karl Lagerfeld, and a few

others who spoke the same language, literally and visually. “We understood each

other,” he recalled. “We were the few who could talk German to each other, everyone

else was English or French.”

When Enninful asked what he now looks for in a subject, Teller’s reply was simple:

“Everything which touches my heart, which comes from life experience. Walking

through the forest with my mother, photographing a cookbook, people who touched

my heart and my intellect.”

It’s the same instinct that led him to Auschwitz, a project he described as a

responsibility, “It took me half a year to recover,” he admitted.

But Teller’s sharpness never dulled when asked about today’s art-fashion circuit,

“They’re desperately eating each other up, bulging out the arm of everything is like

an overdose of this shit.”

For someone known for raw honesty, Teller was remarkably restrained, having said

“fuck” only four times throughout the whole conversation, yes, I kept tabs, politely

rotating through all its conjugations: “fuck,” “fucked,” and “fucking.” That’s fucking (if I

might add) polite, by 90s standards.

He’s not cynical, just precise. His refusal to conform remains almost punk. “I want my

work to be alive,” he said. “Not trapped in a white cube.”

Contracts? They were never part of the plan. “Those young photographers in the

90s, they all swooped to New York and got contracts. You’re handcuffed and you’re

fucked.” He’s worked with Marc Jacobs, Phoebe Philo, Vivienne Westwood, JW

Anderson, Loewe, Dior, and yet, “I never would say I want to have a contract and

have to be doing this. I say yes or I say no.”

That independence, Enninful notes, is rare. Teller smiled: “It’s instinct.” You have to

be clever about what excites you,” he explained. “Other things you turn down. You

need to stay curious.”

Even Enninful, who has known Juergen for over thirty years, acknowledged this

uncompromising clarity. “You’ve always known what you want and what makes you

happy,” he said. “That’s something you’ve really carried on.”

As the conversation continued, Enninful asked, “How can a young photographer in

today’s world, have a singular vision and be able to perfect it?” To which Teller

replied, half-laughing, half-philosophical: “Would one even want to be a

photographer now? It’s a very difficult environment, everything has to be so loud. But

in the 90s, we didn’t mind being poor. We were naïve, enthusiastic, experimenting.

We had time to play.”

Listening to them, I realised I wasn’t just in the audience.

In the 90s, I was in my early twenties, a fashion student in Milan discovering

everything for the first time. I remember the Helmut Lang campaigns, that raw

energy that felt so new. The first time I saw Teller’s portraits and didn’t quite

understand why they felt real. I remember Sinéad O’Connor and Buffalo Stance on

the radio. It all blurred together, fashion, music, and attitude, a cultural moment that

defined how we saw ourselves.

Hearing him speak, I was reminded of the innocence of that time, the creativity born

from having so little. We made things with what we had. There was no fear of failure,

if it worked, it worked. If it didn’t, it didn’t. It reminded me how unpolished everything

was, and how freeing that could be.

It also echoed something I often think about as an educator: how the creative

process itself has changed. Back then, we had to go out and look for things. You

went to exhibitions, record shops, libraries, and galleries; creativity demanded

curiosity. We were hunters, searching for creativity and inspiration by accident, not

by algorithm. Everything happened more slowly and organically. That thrill of

discovering something by accident is missing.

That innocence, that energy, that hunger that made you believe anything was

possible. Today everything feels faster, more direct, but also less surprising. Maybe

that’s what Teller means when he speaks about failure, not as loss, but as freedom.

The freedom to explore, to experiment, before everything became so instantly

accessible.

“We had a deep enthusiasm, and it was a way of living and experimenting and

playing.”

That idea feels almost utopian now to fail without fear, to play without an algorithm

waiting to measure it.

As a last question to the conversation, Enninful asked what advice Teller would give

his younger self. He paused, then said: “Just keep doing what you’re doing. Have

your moral compass right. Even if you’re unsure, be sure of yourself. I wouldn’t have

changed anything.”

It was a moving expression of acceptance rather than confidence. The sense that a

creative life is built on instinct, on following what feels right even when the outcome

is uncertain.

After the conversation, outside the Petit Palais, Teller stood in his grey tee, jeans,

and the now-famous pink sweatshirt thrown over his shoulders, relaxed, grounded,

fag in hand, and disinterested in polish. A bright contrast to my monochromatic

uniform. Maybe that’s what we’ve lost in the rush for polish: the right to be unsure.

It struck me that he hasn’t really changed. The honesty that shaped his pictures in

the 90s, imperfect, immediate, human, is still there.

Maybe the real nostalgia isn’t for the decade itself, but for that kind of freedom. The

90s weren’t cleaner or better; they were just truer.

And that’s the real lesson. Creative integrity isn’t about reinventing yourself

endlessly, but about staying true to the impulse that started it all.

It struck me that he hasn’t really changed. The honesty that shaped his pictures in

the 90s, imperfect, immediate, human, is still there.

Maybe the real nostalgia isn’t for the decade itself, but for that kind of freedom. The

90s weren’t cleaner or better; they were just truer.

And that’s the real lesson. Creative integrity isn’t about reinventing yourself

endlessly, but about staying true to the impulse that started it all.